New Roles for Jones and Akbashev

Danielle Jones, MD, FACP, Professor of Medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine has been named as Chief of General Internal Medicine at Grady Health Systems. In this role, Dr. Jones will provide strategic vision and leadership for Grady GIM, working closely with clinical teams, administrators, and community partners to expand access and enhance the quality of care and safety for Grady’s patients. Her leadership will span hospital settings, outpatient clinics, and community-based programs, ensuring coordinated and patient-centered services across the system. A central focus of her work will be supporting physicians by improving clinical processes, promoting clinician well-being, and strengthening the conditions that allow providers to deliver the highest standard of care.

Dr. Jones is a nationally recognized leader in academic internal medicine. She is the Director of Faculty Development and Promotion for the Emory Academic Internal Medicine Center (AIM Center) and the Associate Program Director in the J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program. She has led multiple initiatives and committees within national professional organizations, including the Society of General Internal Medicine, where she serves on SGIM Council and as Council Liaison to both the Women and Medicine Commission and the Clinical Practice Committee. She has chaired the Grady GIM section’s Faculty Review and Development Committee since 2014 and plans to continue to strengthen and spread the practices of the committee. She has been a driving force behind the system’s progress in faculty recruitment, retention, and promotion, with a particular commitment to advancing the careers of women and underrepresented minority faculty.

Mikhail Y. Akbashev, MD, FACP, Associate Professor of Medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine, has been named Grady GIM Inpatient Medical Director. In this role, he will provide strategic leadership and operational oversight for inpatient medical services, with a focus on delivering high-quality, patient-centered care and strengthening collaboration across Grady to advance clinical operations, quality, and faculty development.

Since 2015, Dr. Akbashev has served as a Unit Medical Director and has developed curricula to train faculty, residents, and students in point-of-care ultrasound techniques. He also serves as Medical Director of the Grady Anticoagulation Clinic and Chair of the Anticoagulation Management Team. His initiatives have significantly enhanced patient care across the Emory system, and his expertise in anticoagulation care is recognized nationally through his service on the Board of Directors of the National Certification Board for Anticoagulation Providers.

Stepping down from the Grady Inpatient Medicial Director role, after many years of exceptional leadership, is Neil Winawer, MD. Dr. Winawer's work has driven key system improvements, most notably optimizing telemetry utilization to enhance inpatient care and hospital throughput. Neil has also been a devoted educator, curating and teaching our Morbidity and Mortality Conference and serving as an editor for NEJM Journal Watch: Hospital Medicine, a testament to his unwavering commitment to advancing the field.

Masor retires after 42 years at Emory

Jonathan J. Masor, MD, FACP, a cornerstone of the Emory Division of General Internal Medicine, has announced that he will retire in October 2025. During more than four decades, Dr. Masor has made a profound impact as a clinician, educator, and mentor, earning the respect and admiration of colleagues, trainees, and patients alike. He currently holds the titles of R. Randall Rollins Professor, Master Clinician, Rollins Distinguished Clinician, and Associate Professor at Emory University School of Medicine.

Dr. Masor first arrived at Emory in 1983 to complete his internship and residency under the leadership of Dr. J. Willis Hurst. Upon completion of his training, he was immediately recruited to the Emory faculty in 1986 and has remained ever since, serving with remarkable consistency, humility, and dedication.

Throughout his 42-year career, Dr. Masor has embodied the ideals of academic medicine. “I liked the science and liked helping people,” he reflects simply, describing what first drew him to medicine. That clarity of purpose has remained constant. While his work has been widely recognized—named the R. Randall Rollins Professor in 2018, a Master Clinician by the Department of Medicine in 2017, and a Rollins Distinguished Clinician in 2013—Dr. Masor has always been guided by his own moral compass. “I can’t single anything out as the most satisfying in my career. I try to be helpful and do what I believe I would want others to do for me and my family.”

The names of the publications and awards may have changed over time—Atlanta Magazine, Castle Connolly, Atlantan Magazine—but the annual praise Dr. Masor’s work has earned as a Top Doctor remained steadfast for a 30-year span. He also received national recognition in Town and Country Magazine as one of the Best Primary Care Doctors in America in 2000. Although many were aware of his excellence as a physician, his enduring impact is perhaps best captured by those who have worked beside him.

“After nearly four decades of devoted service to patients, primary care physician Dr. Jonathan Masor is retiring, leaving behind a legacy marked by clinical excellence, deep compassion, and a tireless commitment to patients and students,” says Ted Johnson, MD, MPH, Paul W. Seavey Chair and Chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine. “A consummate physician and dedicated professor of medicine, he exemplified the ideals of lifelong learning, always curious and caring. His extraordinary career and consistently outstanding patient satisfaction reflect an inspiring devotion to the healing professions. We celebrate him with immense gratitude and admiration.”

Dr. Masor’s professional life has been closely tied to the Seavey Clinic, where he worked for many years alongside the late Paul W. Seavey, MD. He helped shape and uphold the clinic’s culture of clinical excellence, emphasizing meticulous attention to detail, adaptability, and patient-first care. “It has been an honor to care for our patients, says. It has also been a wonderful experience to participate in the education of our students and residents. In addition, I have been able to continuously learn from our talented colleagues and be close to the amazing evolution of medicine over the last 42 years,” says Dr. Masor.

Known as a role model for careful and thoughtful medicine, Dr. Masor has left an indelible impression on countless learners. He has also helped the field evolve, adapting to sweeping changes such as the increased role of technology in patient care and documentation.

David Roberts, MD, Charles F. Evans Chair and Director of the Seavey Clinic, reflects on Dr. Masor’s influence: “Jon and his style of medicine have been at the very heart of the Seavey Clinic—what it has been, what it is, and what it can be. He is an incredibly thorough, careful, and brilliant doctor. He is highly regarded as a teacher, with his students often marveling at his ability to give a very detailed talk on a subject with no prior preparation or planning—just digging deep into his many years of experience and remarkable memory. He will be sorely missed and irreplaceable, but his legacy will certainly persist for a very long time.”

As Dr. Masor approaches retirement, his reflections are consistent with the values he has lived by throughout his career. “It is my greatest hope that internal medicine will continue to thrive and that the next the generation of physicians will continue to incorporate the ever-evolving science of medicine with the personal qualities that will emphasize the wellbeing of our patients.”

He concludes with characteristic humility and openness: “I will always be grateful to Emory for accepting me into their internal medicine residency program in 1983, giving me the chance to work with amazing colleagues, continuously educating me, and most importantly making it possible to care for our patients in what has been my life’s work.”

Dr. Masor’s legacy at Emory will endure in the generations of physicians he has taught, the patients he has cared for with unwavering dedication, and the example he has set of excellence grounded in humility and purpose.

Partin retires after 32 years

Retirement Celebration for Dr. Partin

Clyde Partin, Jr. MD is retiring after an extraordinary 32-year career on the Emory faculty. An Emory alumnus (78C, 83M, 83MR), Dr. Partin practically grew up on Emory’s campus, where his father Clyde “Doc” Partin served on the Emory faculty for over 50 years as athletic director and professor of physical education.

Clyde Partin Jr. returned to Emory after serving as a staff physician and flight surgeon for the U. S. Air Force. He was hired by Dr. Paul Seavey and later was instrumental in the creation of the Seavey Comprehensive Clinic. He also founded Emory’s Special Diagnostic Clinic. Dr. David Roberts, Director of the Seavey Clinic, describes Partin as “the heart and soul of the Seavey Clinic – a trusted and revered doctor who is loved and looked up to by his colleagues, patients, staff, and students. He’s one of the most highly sought after and respected clinicians in the Southeast.”

During his years on faculty, Dr. Partin brought his lifelong interests in history and literature to the curriculum as co-director and teacher for the Medicine and Literature elective (2014-present) and as co-founder, coordinator, and moderator of the J. Willis Hurst Annual Symposium for the History of Medicine (2004-present). He served on the Board of Emory University Library’s Special Collections and held key leadership roles in the American Osler Society, including serving on the Board of Directors and as President. He has served on the Atlanta Medical History Society Advisory Board and Governing Board. The same irrepressible curiosity that led him to establish and direct the Special Diagnostics Clinic is reflected in his scholarship; he published an article on “Magic, Medicine, and Harry Potter” and lectured on “Hank Aaron, Home Runs, and Hate Mail” at the Cooperstown Baseball Hall of Fame 16th annual Symposium on Baseball and American Culture; and “The 1969 Woodstock Music Festival: A Public Health Perspective on Peace, Love, and Music” at the American Osler Society Annual Meeting. Dr. Partin has been recognized with many teaching and service awards throughout his career, most recently the Emory Primary Care Consortium’s Career Achievement in Primary Care and the Emory Medical Alumni Association Lifetime Achievement Award in 2023.

Congratulations and best wishes to Dr. Partin on his retirement.

Dr. Partin Looks Back on His Career

How I Ended Up at Emory

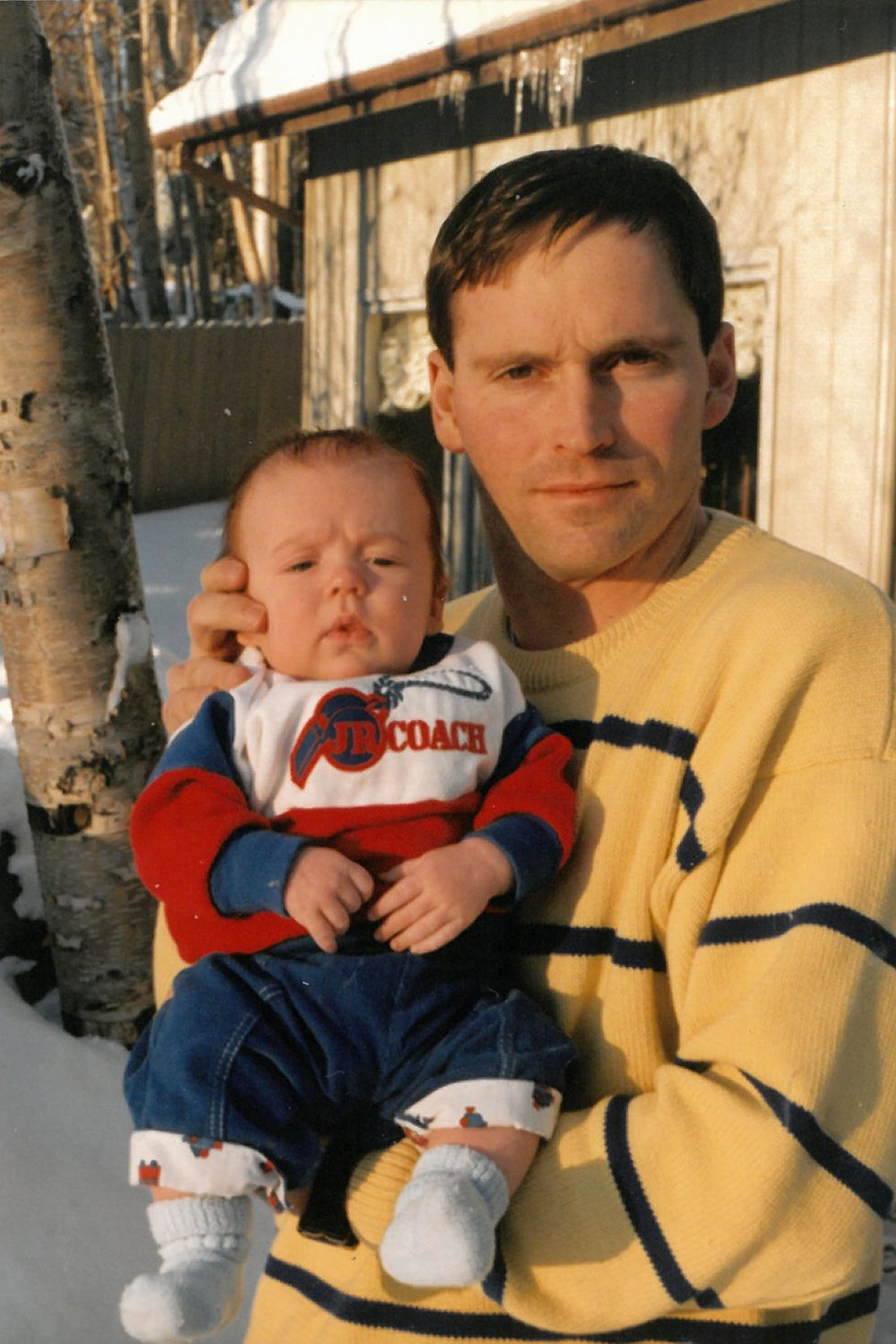

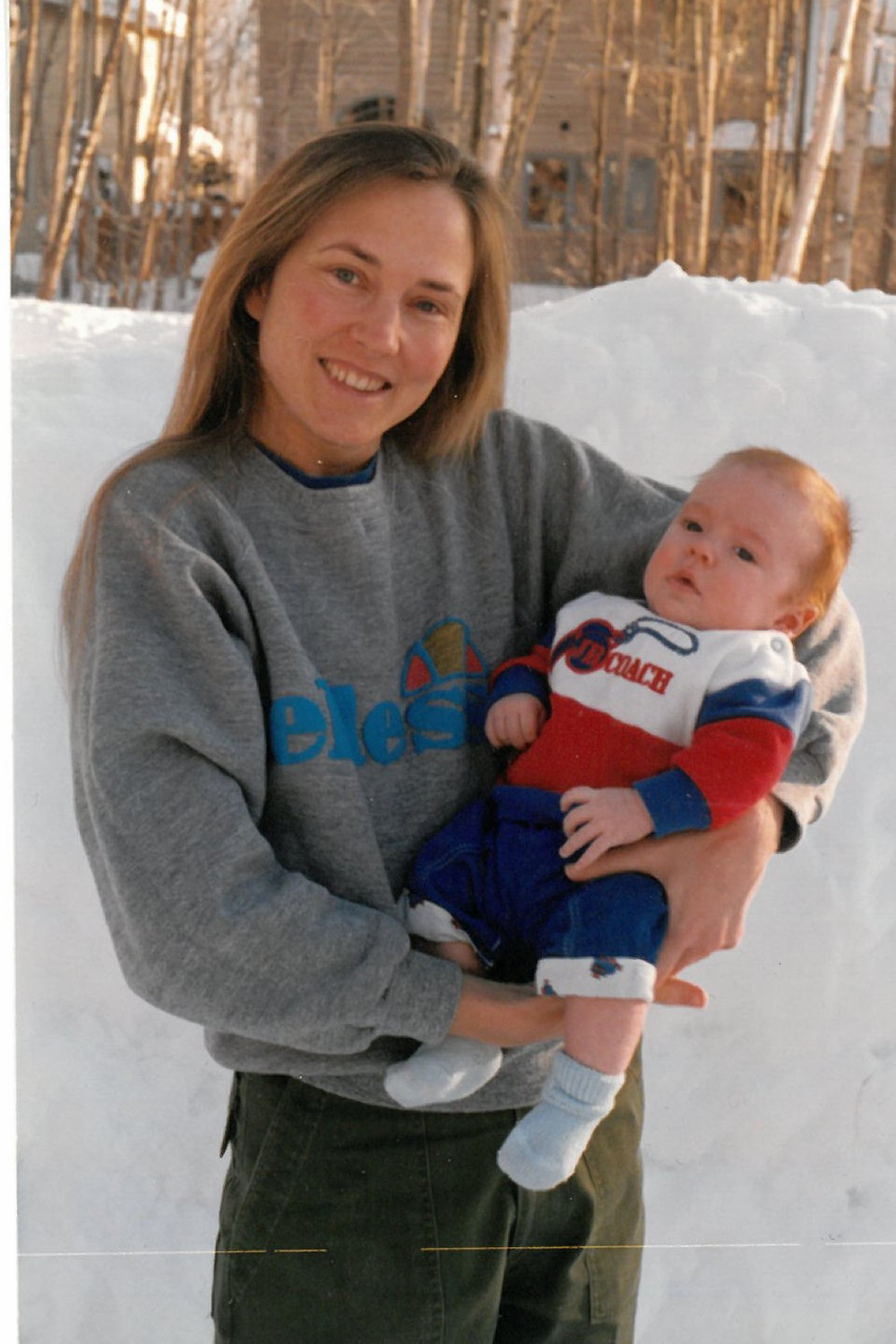

To be a general practitioner in some small to moderate size town was my aspiration. Had you told me when I was in medical school and during my training at Emory that I would end up on the faculty of Emory School of Medicine, I would have found that somewhere between the intersection of ludicrous and amusing. Toward the end of my residency Dr. Paul Seavey asked me if I would consider joining the Emory Clinic, an invitation that took me off guard. Advising him that I had a four-year US Air Force commitment to serve, he replied, “Call me when you get done.” I had joined the Air Force for two valid reasons. One was the issue of how to pay medical school tuition. Two, I really wanted to be a flight surgeon and find out what it was like to fly in high performance aircraft. My first duty station was Plattsburgh AFB in upstate New York. After having spent the first three decades of my life in Atlanta, I had written across the bottom of an Air Force form, "Get me out of the Southeast," in response to being asked where we might want to consider being sent. My wife Kim, a clinical microbiologist, found a lovely job in Burlington, Vermont at their medical center. Three years later we were transferred to Elmendorf AFB in Anchorage, Alaska. While driving out to Alaska, we passed through Missoula, Montana and visited a friend practicing cardiology there who encouraged us to consider coming back to set up practice, an idea of which my wife approved. Things apparently went different directions after that. This is where I give my wife credit for getting me back to Emory although I do not think she ever quite realized it. Our first child was born in Alaska. Kim acquired a microbiology job at the hospital in Anchorage (She became an expert in identifying what organisms infect bear bite wounds.) She took our son to the hospital where they had a superb daycare center.

Then this happened. About twice a year, I was asked to go investigate some medical mishap. These trips lasted two or three weeks but I enjoyed acting like a detective trying to solve these problems. And there were many other shorter trips with which my wife had to contend. In late November 1991, the Air Force sent me on a three-week trip to the Philippines for a multinational military exercise. Physicians were there to take care of our own troops plus Mount Pinatubo volcano had erupted, resulting in a number of refugee camps for people displaced by the eruption. Every day we rode out to remote mountain sites to take care of these people. In the evening, we returned to basecamp, right on the edge of the beach in what turned out to be a resort town. We discovered a nearby luxury hotel, and the medical staff gathered there each evening for conviviality. This was all tropical and quite lovely. Returning to the Air Force Base about four AM one morning in mid-December, minus ten degrees, it took me a while to get back to my car, now decorated with about five feet of snow. Finally I made it home about six AM. My wife was getting my son ready to go to daycare. She handed me s snow shovel and said, in a frosted tone, “Your turn.” That evening, she reported, “I think we should consider getting out of the Air Force.” She did not exactly say that we should go back to Emory but she did exactly repeat that it was time to get out of the Air Force. Remembering what Dr. Seavey had told me, I called him and he invited me for an interview with him and Dr. Kokko. Here I am 32 years later. So I thank my wife who steered me back to Emory even though she may not have fully intended to do so but turned out she gave me superior advice.

We have had quite a ride at Emory, surrounded by accomplished colleagues and staff in the Seavey Clinic. The leadership provided by Dr. David Roberts has been extraordinary, who eventually took over the Seavey clinic and steered the clinic to the next level and beyond. The opportunity that has been provided to teach students and residents, the support to pursue my interests and write about the history of medicine, and practice medicine has been a remarkable experience. Supervising medical students and residents in the hospital and clinic has been most gratifying. My interest in flight medicine allowed me to do spend twenty-five years performing Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) exams. The opportunity to develop and manage the Undiagnosed Illness and Rare Disease Clinic was a real game changer for me. The intellectual stimulation and maturation this clinic provided me challenges and abiding satisfaction. This also made me a better physician. I was able to collaborate with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rare Disease Program and came into contact with the world’s best geneticists. For the record, in this Diagnostic Clinic, I tried to project an image of Sherlock Holmes because people began calling me Dr. House, which was disconcerting because he was such a jerk.

Again, I am deeply indebted to Emory and its leadership and the opportunities that have come my way courtesy of this affiliation. And for the role my wife played in my career. As a last thought, I humbly offer the same advice I give myself: Be curious, keep asking why, and read widely every chance you get.

21 June 2024