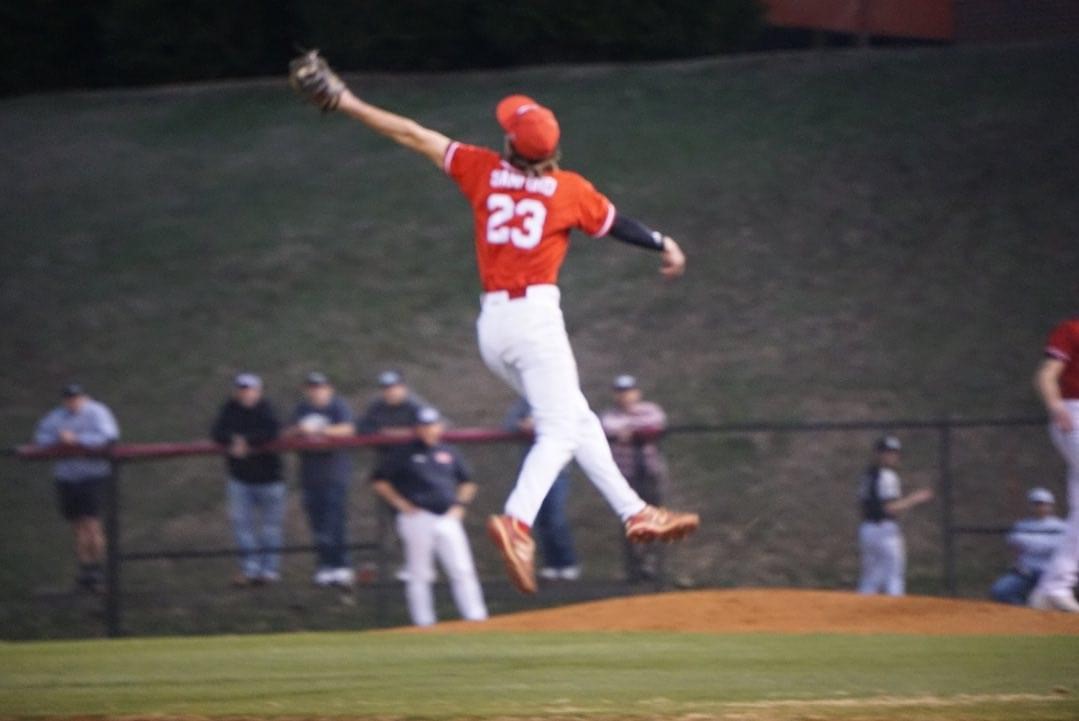

Google the words “Layton Sanford” and the long-held dreams of a Silver Creek, Georgia teen will pop up before you finish typing.

Baseball.

“I would like to make it to the major leagues,” says the soft-spoken 18-year-old pitcher for the Pepperell High School Dragons and the Nelson Baseball School travel team. “That’s the plan, anyway.”

That plan is manifesting nicely. Last fall, Layton accepted a full baseball scholarship at Snead State Community College in Boaz, Alabama. After that, he has choices. Good choices.

“I’d like to play ball for a bigger college, or maybe even get picked up by the minor leagues,” Layton says. “Or I could continue studying, probably engineering.”

His father, Nolen Sanford, points out that Snead got a great deal.

“I mean I don’t want to boast, but he’s not just baseball. He’s a lot of other things you’d hope your kid would be: National Honor Society, 4.0, AP Honors, even Homecoming Court…”

Nolen pauses as his son stares a hole into the floor.

“I guess we forgot to tell [Snead] that you only have sight in one eye, didn’t we?“

Father and son laugh.

“But I don’t think they asked either.”

Layton Sanford is one of the hundreds of patients that Emory Eye Center ophthalmologist Baker Hubbard, MD has diagnosed with retinoblastoma over the last 25 years. Like most of Hubbard’s patients, Layton was too young to remember anything about the disease that took sight from his right eye. His parents will never forget it.

Recalls his mother, Michelle:

“When he was first diagnosed, there was a lot of wondering; ‘What will he be able to do? What will this mean for the rest of his life? We were so frightened,” she says.

“But Dr. Hubbard was right there, telling us that we had to allow him to grow up, to do kid things. Wear protective gear, goggles when he plays sports, sure, but don’t stop him from being a kid. The only thing he wouldn’t be able to do is fly an airplane off of a boat.”

Nolen laughs at this last piece of advice.

“Well, I guess that’s something that you might do in the Navy – fly a plane off of a boat,” he explains. “But Layton’s got a whole lot of other things he can do.”

Hubbard’s words gave the Sanfords something upbeat to hold onto as they navigated 18 months of retinoblastoma treatment and a childhood that would end up looking a lot like everyone else’s.

Except, perhaps, this: Among high school athletes, Layton Sanford’s pitching is ranked fourth in the state.

“I don’t remember much about treatment,” Layton adds. “And for me, this was always the way it was. Not having sight in one eye didn’t make a difference. [He smiles] Yeah, I remember asking one of my friends ‘What’s the use in having two eyes if you can only see out of one?’ I couldn't understand why I would need two.”

At this, his parents laugh.

“We worked hard to make sure he had a normal childhood,” says Michelle. "This is normal."

-Kathleen E. Moore