1872-2022: Still healing. Still teaching. Always learning

When we sat down to contemplate what a century and a half has meant to the Emory Eye Center, we quickly concluded that our history has transcended the narrow rectitude of calendar logic. At 150, the Emory Eye Center is more than a timeline of key dates. It is, in fact, a dynamic mission that has for generations inspired us to take smart risks and pursue cutting-edge solutions in our clinics, labs, classrooms, and community.

How do you summarize all that?

Quite simply, by recognizing that it's the people behind the Emory Eye Center who have made our mission relevant. To celebrate our 150th anniversary in 2022, we turned to four individuals - F. Phinizy Calhoun III, whose story is below; longtime supporter, Debra Owens; one of our global partners, Dr. Tiliksew Teshome Tessema; and the reigning chair of the department, Dr. Allen Beck . Together, their reflections on the Emory Eye Center's story inspire us to embrace the challenges that will come in the next 150 years.

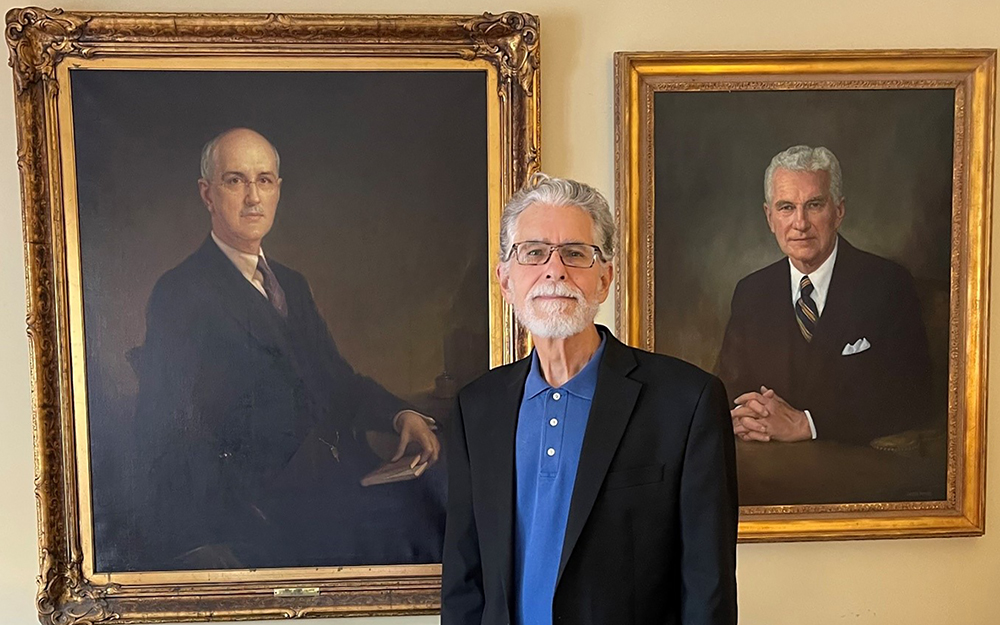

Revisiting Our Roots: F. Phinizy Calhoun, III

Two academic chairs are endowed by the Calhoun family. But tenacity and character were their most valued gifts to the Eye Center's legacy.

If Emory Eye Center had a maiden name, it would be Calhoun. The forefathers of this institution -Andrew B, Abner W., F. Phinizy Sr., and F. Phinizy Jr. - carefully built and faithfully curated what is now a world-renowned medical service and teaching facility. Taken together, their leadership in the department spans almost half our 150-year history.

We gained insight into what made these pioneers tick during a recent visit to F. Phinizy Calhoun, III [Phinizy III] - son of F. Phinizy Calhoun, Jr., [Phinizy Jr.] the chair of the department of ophthalmology from 1946 to 1978. Now retired from his own career in the film industry, Phinizy III spoke with candor and reverence about his father's commitment - to patients, to medicine, and to identifying a passion that would last him a lifetime.

My father never told me I had to go to med school or pursue ophthalmology,

he said. That was his thing. He worked hard and with exacting precision at it. He wanted me to find my own path. To pursue my own passion with as much energy as he did his.

Early on, young Phinizy III learned that this would be a high bar to clear.

When I was a young boy, I remember on Sundays, after church, the whole family would drive straight to the Emory University hospital so my father could visit his patients. He left the entire family in the car, waiting, sometimes for an hour or more. There wasn't any air conditioning in those days, so it was hot and stuffy. And we [Phinizy and his two siblings] got fidgety after we'd finished the Sunday comics. But there were no complaints or apologies when he returned. We knew that to be a doctor meant you were always concerned with the patients.

Phinizy Jr.'s dedication didn't end with his rounds. Working with the then-chair of the department, Grady Clay, he organized one of a handful of ophthalmic pathology labs in the country - a place where he and other physicians could exhaust their curiosity and investigate new treatment approaches.

Understatement was his statement

If Phinizy Jr.'s children were, at times, captives to this educational odyssey, they were also its beneficiaries:

When I was still in elementary school, my father used to bring home photo stills and 16-millimeter films of his surgeries. He would close the curtains in the living room, set up a four-by-six-foot screen, and invite us to watch them. Sometimes, he'd joke with us by telling us that he was going to show us Woody Woodpecker cartoons.

[laughs]

And he'd usually show the cartoons, but I stuck around to watch the surgery films, too. For him, they were fascinating. He analyzed everything with enthusiasm. For me, these movies turned me off to the blood, the cutting, the surgery part. I didn't think that was so cool. Instead, the impression it made on my young brain was that a dark room with a projector could import magic into a room. I began to imagine what I could do with film. That's really, you know, how I found my career.

The elder Calhoun's interest in the fledging field of ophthalmic photography rubbed off on Phinizy III, and his sister Mary Ellen, both of whom did some photography for the Emory Eye Center as young adults. Eventually, Mary Ellen went on to become a teacher but Phinizy III parlayed the experience into a career as a video producer/cameraman. Their other sibling, Marion Peel, became a professional photographer.

As his career progressed, Phinizy Jr. became a towering figure in the field of ophthalmology. His kids were none the wiser. The elder Calhoun was the first doctor in Georgia to perform surgery under a microscope; the first doctor in the Southeast to perform a corneal transplant; and the driving force behind the establishment of an eye bank – one of only five in the nation.

Phinizy III and his siblings were, for the most part, clueless about their father's growing celebrity They knew that other ophthalmologists from around the country would send patients to their father. But, to them, Phinizy Jr. was a devoted family man, an amateur musician, a part-time genealogist. A dad.

My father never name-dropped about his famous patients or made a big deal out of his many accomplishments or national reputation,

Phinizy III noted. Understatement was his statement.

Hard work is never the enemy of a visionary

It wasn't until Phinizy Jr.'s funeral, in 1995, that the world got an unfettered glimpse into the character of this iconic figure. A lifelong friend, George Hightower, gave a eulogy that Phinizy III recalled to us:

To earn an Eagle Scout badge, a then-17-year-old Phinizy Calhoun Jr. was tasked with riding his bike from Buckhead to Duluth - a 50-mile round trip. In those days, some roads were no more than dirt paths, so it was going to be a rough ride. As he was about to set out, he discovered that the seat on his bicycle was not attached securely. So he would have to ride most of the way without sitting down.

Well, he did it, and he was back by sundown, exhausted,

said Phinizy III.

But the next day, when he went to the Boy Scout Headquarters to report his accomplishment, the scoutmaster told him he wouldn't get the badge because he hadn't also mailed a postcard - signed by the Duluth postmaster. Phinizy was disappointed, but undeterred. He recognized the importance of following directions and he sorely wanted to earn that badge. Instead of complaining, he asked if he could complete the trip the following weekend, only this time, to Stone Mountain and back. It was the same distance, and still not an easy ride. But he chose it because he 'wanted a change in scenery.'

He earned that badge, of course, and went on to quietly change the scenery for many generations to come.

--Kathleen E. Moore

Read more about our history!