Physicians are always in short supply in rural areas, and in 1979, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine expected its new graduates to fill that need. One who rejected that path was Daniel L. Barrow, who specialized in neurosurgery and became Emory’s foremost brain surgeon.

But the yawning need and extraordinary benefits of rural medicine nevertheless remained constant in Barrow’s life because of his father, a general practitioner serving patients scattered across farms and towns in southern Illinois, about an hour north of St. Louis. His father’s practice left a permanent imprint on how Barrow practices brain surgery and trains residents, and represents the immense potential opportunities, influence, and legacy for a physician serving a small community.

Showing up for generations of many of the same families, Warren C. Barrow (1929-2013) honed diagnostic skills that still blow away his son today. Dan Barrow, age 69, credits his patient relationships, longevity, and work-life balance to observing his father thrive in the close proximity and community demands of a rural practice.

“The kind of doctor he was, he had seen everything twice and had to manage it, without relying on a lot of fancy tests like we do,” Barrow said. “He was curious and constantly challenged himself to go out and learn new techniques, to get better at reading EKGs, at diagnostic maneuvers, or learning about new drugs. Constantly. He was the greatest doctor I have ever known.”

Why not primary care?

Primary care doctors are often taken for granted in a culture that confers greater pay and status for specialists like brain surgeons. Dan Barrow points out another unsung differential: personality.

His father enjoyed doing physical exams and telling people they were fine; those kind of interactions exhausted Barrow. “I like taking care of very sick people,” he said.

Both father and son would have to cope with loss distinct to their practices: Warren Barrow with the typical deaths in a community across 50 years, and his son with the high mortality rate of patients with serious brain issues.

“I have to walk that thin line between being so cavalier, cold and heartless, and the other extreme, being so devastated by a complication, you can't get up the next day and go back to work,” Barrow said. “My father had a different level of ownership, and for 50 years I watched how he dealt with families with losses, and victories and failures.”

His father had to read all of his x-rays, and when a radiologist who over-read his imaging once a week pointed out something he missed, Warren Barrow responded by trying to learn more. “He was a very compassionate person,” his son said. “He was always asking, 'What can I learn from this to make sure that I do better for my patients in the future?'”

This exceptional drive and curiosity today influences Emory medical students and faculty who attend the regular morbidity and mortality conferences for neurosurgery.

“We painfully go through every single complication in a case, and everybody in that auditorium feels perfectly comfortable,” Barrow said. “Any one of the most junior residents can ask, ‘What in the world were you thinking? Why did you do it that way?' By asking, 'How can we do this differently?” you walk out of the room and do better in our work. My dad had one partner in his practice, and they asked themselves questions like these."

Every specialty rolled up in one practice

Warren Barrow never considered moving from serving Pike and Calhoun Counties and the hub city of Pittsfield (pop. 4,200 then and now), though he did pack up his wife and four kids each summer for epic road trips to national parks and historic sites across North America and Mexico. He loved history and saw his role on par with a teacher or any public servant, except for his hours. When someone had a heart attack at dinner time or a woman went into labor at 2 am, he reported for duty.

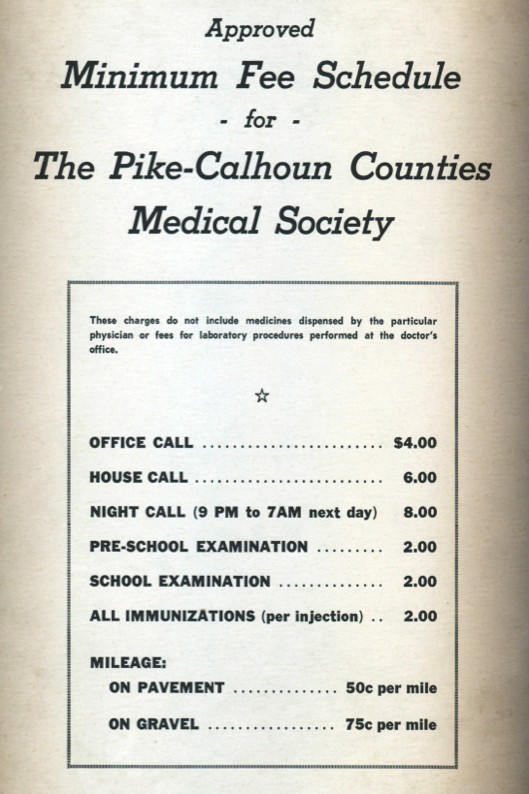

At one point, he charged $4 for an office visit and $6 for a house call, with 50 cents a mile except on gravel roads. On that terrain, he charged 75 cents a mile.

“His generation of physicians is a vanishing breed,” noted his obituary in the local paper. “He was not only a general practitioner, but the cardiologist, gynecologist, obstetrician, emergency room physician, urologist, gastroenterologist, pulmonologist and psychiatrist for his patients. Throughout most of his career, he was on call every other night to manage all levels of routine, urgent and emergency medical services, including house calls, delivering babies and covering the emergency room at Illini Community Hospital.”

From Oct. 27, 1961, to the same date in 2011, Barrow's typical weekday involved seeing 40 patients. “Some of them would be nothing more than checking their blood pressure, rewriting their prescription for their hypertensive or asthma drugs,” his son recalled. “He really loved the variety.”

Calling More of the Shots

Warren Barrow also loved being a practical, essential resource to his neighbors, almost like a reliable car mechanic, in an area where most people's livings depended on pigs, corn and soybeans. His own father, Adlai “Doc” Barrow, had served this area as its only dentist, who opened at 6 am to treat farmers.

Warren Barrow made decisions that many physicians today would not be comfortable making, his son recalled. He never faced a malpractice suit in 50 years either.

“Some of the things my dad took care of were out of necessity because people didn't have the resources to just drive to St. Louis, the nearest academic medical center They maybe couldn't afford the gas. So he really had to fix problems,” Dan Barrow said. “Obviously, he referred patients to specialists for their hip surgery and for their complex cardiac problems, but out of necessity he took care of everything else, and he felt comfortable doing that.”

Memorizing critical information such as drug interactions was necessary because mobile and online resources did not exist for most of his career. When he was on call, he had to be near a phone, and he missed many of his son’s sports events because the football and basketball venues lacked a landline. Liberation came with his first pager, a big metal box that he carried around and emitted a signal to return to Illini Community Hospital.

He referred the most challenging cases to the closest specialists at the state medical school, and when Dan Barrow was a student there, some of those physician faculty told him that his dad was “one of the best doctors we’ve ever seen. Whenever he sends us a patient, they really need to be seen.”

“He was really recognized as somebody who took care of everything, but knew his limitations,” Dan Barrow said. “That's an art.”

One form of preventive medicine was taking his young son to see certain accident victims in the emergency room at Illini Community Hospital. “I was a little boy seeing these people's broken limbs and broken necks and all bloodied up,” Dan Barrow said. “I grew up with this extraordinarily healthy fear of motorcycles. The fear of God, really.”

Where the quail are

He returned to Chicago to do one year of internal medicine residency at Presbyterian St. Luke's Hospital when his son Dan was in second grade, but Warren felt urban life confining, so he moved back home to Pittsfield to replace a local general practitioner who had died when thrown by his horse. Driving to Illini Community Hospital took four minutes and traffic never existed. During dinner with his family, he could leave to check on a patient and return before the end of the meal.

Rural life also meant he could easily pursue hobbies that made him happy with people who treated him as an equal and pets who adored him.

In his medical office, he kept a county plat book where he marked locations that his patients had seen quail and where he was welcome. “There were thousands of acres where he could hunt, and we would eat quail, duck, rabbit, and squirrel,” Dan Barrow said. A resolution passed by the Illinois State Senate in honor of Warren Barrow's lifetime of service noted that “one of his most cherished times of the year was the Labor Day weekend dove hunt; he liked to tell hunting stories and had several generations of hunting dogs who were his loyal companions throughout his life.”

“He was a humble person,” said Dan Barrow, a hunter with a second home in rural Jasper County, Ga. “Some of his best friends were dirt poor farmers he loved to hunt with, who would pay him with eggs, cream or venison.”

Another fundamental change over the years was how his work was described. For most of the 20th century, a general practitioner like Warren came to mind when anyone in his community used the word “doctor.” His training in internal medicine was part of being a general practitioner back then.

But as specialization transformed the practice of medicine, physicians referred to themselves less often as general practitioners (from 83 percent in 1931 to 18 percent in 1974, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.) Today, Warren would be called a family physician.

Inspiring generations

His legacy today includes Dan Barrow and two of Barrow’s three children: Emily Barrow 14M 19MR, assistant professor in the Division of Rhinology and Skull Base Surgery in the Emory Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, and Jack Barrow, a radiology resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. In medical school applications, both wrote about the influence of their grandfather, whose diagnostic prowess always awed them.

As a young boy, Jack Barrow was running a 102 degree fever and Warren Barrow answered the call from his son. Was there a bumpy rash, he wanted to know. When told yes, he correctly diagnosed scarlet fever—over the phone.

“Whenever they would get sick, my kids would come to me and say, 'Daddy, I don't feel good. Call Grandpa Warren,'” Dan Barrow recalled, laughing. "Truthfully, they knew that I was not a real doctor. I can offer insights about research, but I can't take care of a cold."

Warren Barrow continues to influence his son’s neurosurgery practice and way of life. He is fastidious about updating his patients’ primary care doctors because his father looked down on specialists who didn’t communicate.

Dan Barrow and his wife Mollie Winston Barrow, an oral surgeon, open their home to a medical school student with financial need (supported by the Suzie C. Tindall Medical Scholarship Endowment), and a recent student is now following in the footsteps of Warren Barrow.

“Her family lives at the end of a long dirt road in rural South Georgia,” Dan Barrow noted. “She considered every specialty in medical school, but her dream was to go back to this community that she grew up in general practice. I talked to her about my dad and encouraged her to follow her dream.”

Two lasting messages

Forever etched in his mind are two conversations with his father, and these memories remind him of the value of full commitment to patient care for rural families, people with complex brain tumors, or anyone else.

The first dialogue unfolded in the late 1970s when Dan broke the news that he would specialize in the obscure field of neurosurgery. “Why would anyone do that?” his father snapped, before adding that whatever type of doctor he chose to be, “Be a good one.” What kind of physician his son chose to become was less important than why and how he treated people in need.

The second conversation was their last, in 2013. “Retirement sucks,” his dad told him. Age-related macular degeneration made Warren Barrow fear "that his vision would make him miss someone's rash, or that he'd make the wrong diagnosis," said his son, who aspires to have the same courage.

“I love what I do and I’d love to do it till I die,” Dan Barrow said, “but I don’t want to wait until one of my partners puts their arm around me and says, ‘Hey, Dan, we have to have a talk.'”

For most of his career, Warren Barrow was on call at Illini Community Hospital, which local citizens funded and built between the Depression and World War II. For a half-century, it was where he admitted any patient that needed it. Finally, at 84, that patient was himself, and this is where he died, in the healthcare hub of a rural community that needed him and that he never wanted to leave.

Dr. Daniel Barrow is Pamela Rollins Professor and Chair, Department of Neurosurgery, Emory University School of Medicine. He completed his general surgery internship at Emory in 1980 and finished his neurosurgical residency at Emory in 1985.